Intergenerational Mobility in South Asia

Sam Asher, Aditi Bhowmick, Maurizio Bussolo, Paul Novosad

May 2022

May 2022

South Asia is one of two regions with the lowest intergenerational mobility across developing countries (Narayan and Van der Weide, 2018). A perfectly mobile society is one where the socio-economic outcomes of individuals are unrelated to the corresponding outcomes of their parents. Persistence of parochial historical social structures such as the caste system across South Asia (Jodhka and Shah, 2010) is linked to low intergenerational mobility in the region. Among other things, the caste system mandates that a barber’s son will remain a barber. This creates artificial barriers to upward mobility that are unrelated to the changing landscape of economic opportunity. However, growth of economic opportunity and widespread access to education can erode intergenerational rank persistence.

We estimate intergenerational education mobility across time, space and communities for seven countries in South Asia. We draw on thirty-nine national representative household surveys to create a harmonized dataset with matched parent-child education attainment for India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. We apply a new measure of intergenerational mobility suited to data-constrained developing country contexts to study upward mobility in South Asia. This is the bottom half mobility measure, developed by Asher at al. (xxx) for the study of intergenerational mobility across space, time, and communities in India. Bottom half mobility describes the education outcome of the average child born to parents in the bottom half of the parent education distribution. Background on how this measure circumvents the issue of coarse income and education data in developing country contexts can be found in the methods section of the working paper.

Our results suggest a distinct hierarchy of countries in the South Asian region in terms of intergenerational mobility, with Bhutan at the top and India at the bottom of the ladder.

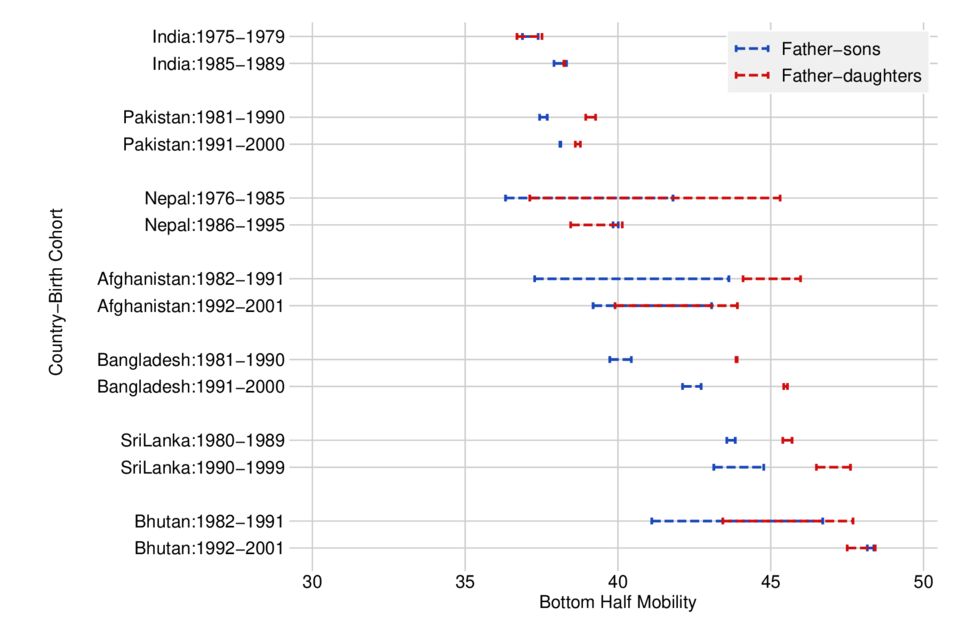

Note: The figure above shows bounds on bottom half mobility for males and females in each country in our sample. For each country, selected birth cohorts have been displayed in the graph to illustrate the change in mobility across South Asia over a broadly consistent time period.

South Asia is a particularly interesting region for the study of intergenerational mobility for a number of reasons. First, South Asian countries present substantial variation in social structures such as persistence of caste, religious composition, and historical gender norms. Second, South Asian countries have followed divergent political-economic trajectories since decolonization, resulting in variation in access to education attainment and economic opportunity within the region. Third, a quarter of the world’s population and a third of the world’s extreme poor live in the region. The interaction of upward mobility and growth in economic opportunities has implications for the degree to which the 216 million South Asians living in extreme poverty can partake in the returns from growth in the region.

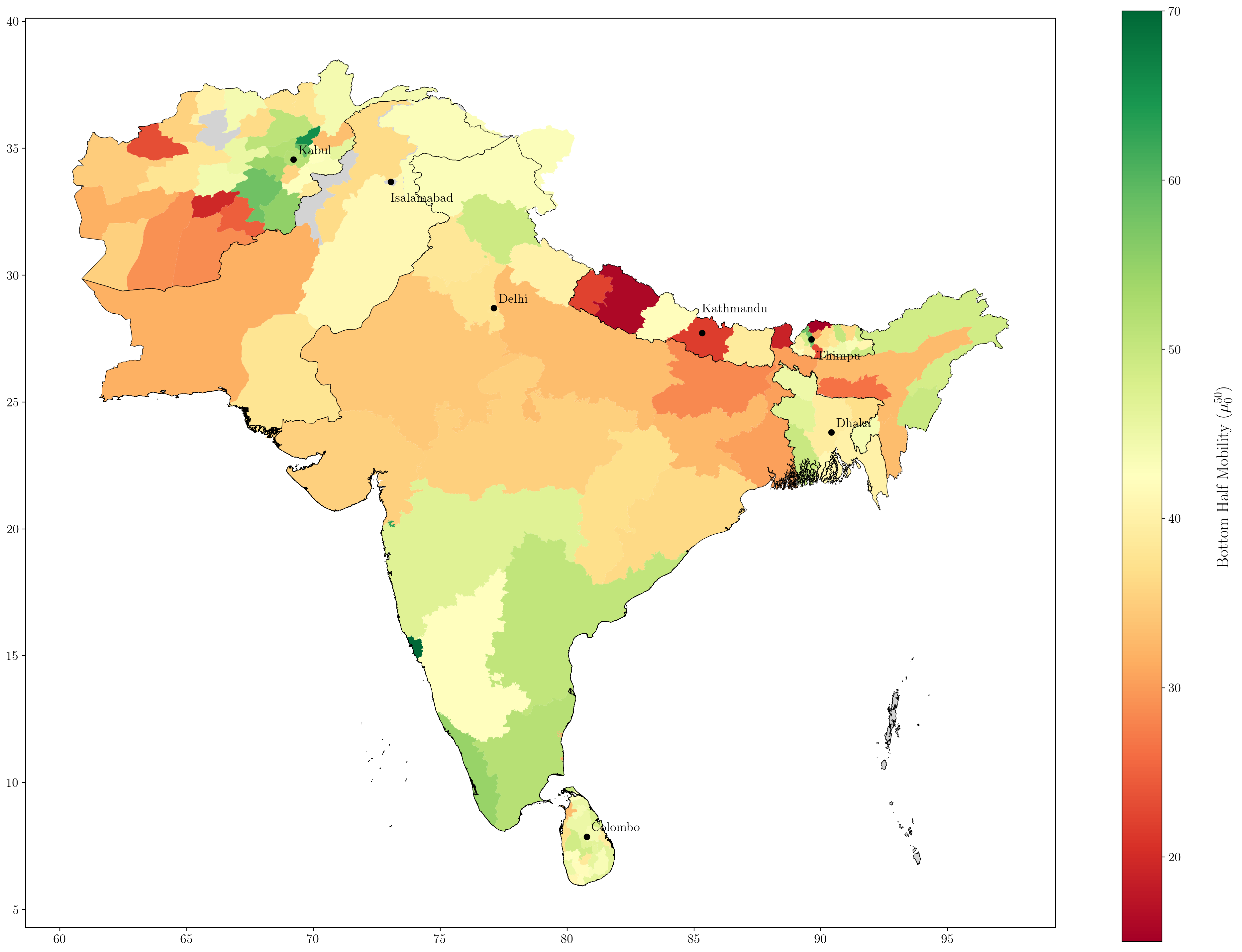

National mobility measures mask substantial underlying variation in upward mobility by geography and social groups. For instance, some Indian states such as Goa and Kerala exhibit upward mobility as high as Sri Lanka for both men and women whereas others have mobility as low as regions historically dominated by the Taliban in South Afghanistan.

Note: The figure shows bottom half mobility for matched father-son pairs at the subnational level for each country in our sample. Note that the parent and child education ranks are calculated within a country, birth-cohort group for men and women separately.

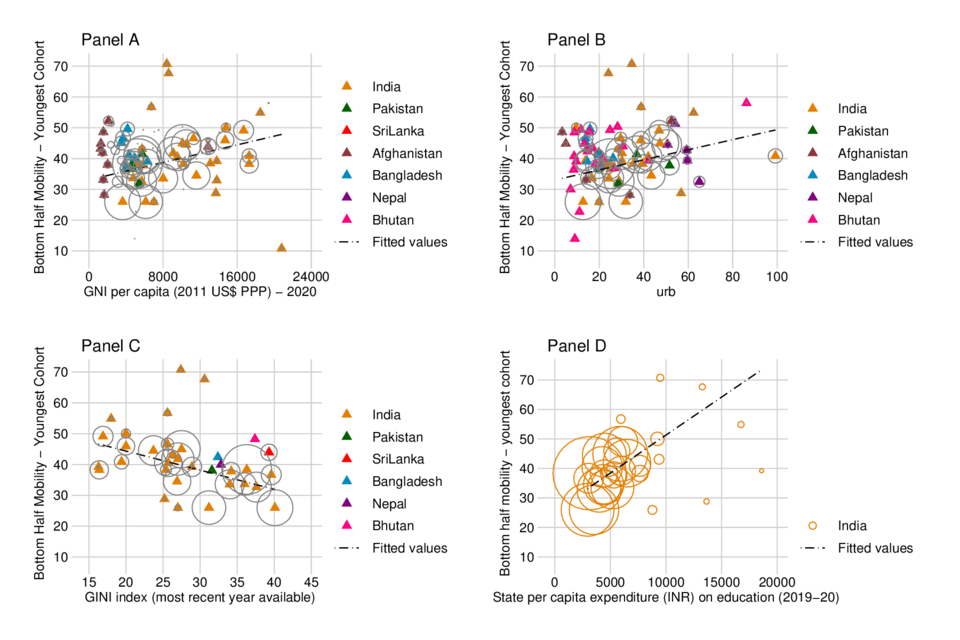

We find bottom half mobility moves in the same direction as income per capita, urbanization, top half mobility, learning outcomes and public education expenditure. Regions with high income inequality are ones where upward mobility is limited among the poor.

Note: in Panels A-C, the national economic indicator was used when sub-national data was not available for the country. Panel D is restricted to subnational units in India since the comparable measure for the other countries in our sample was not available.

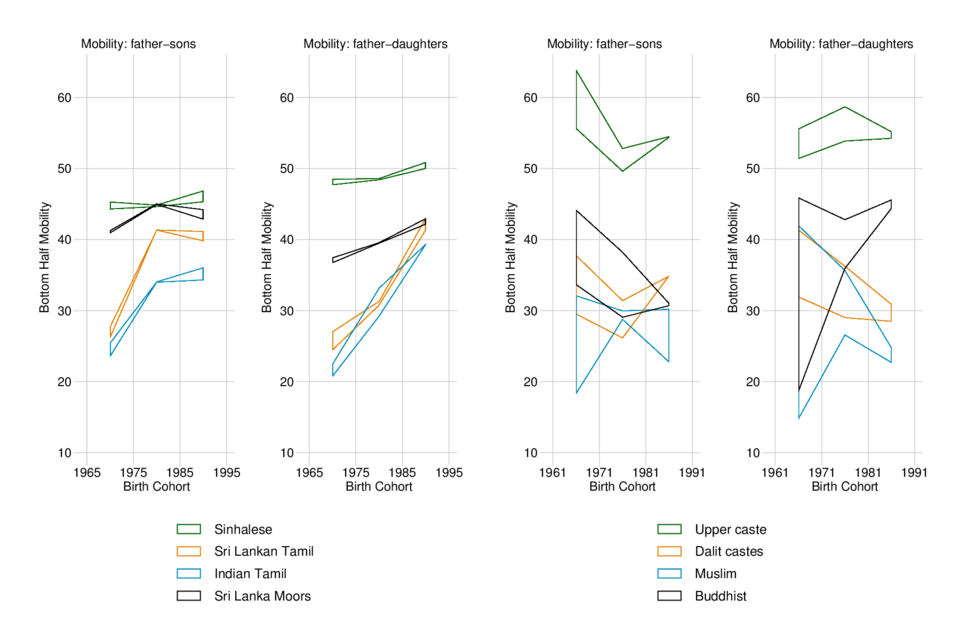

Finally, Mobility gaps across social groups such as religion, caste and ethnicity vary across countries as well. Bottom half mobility across social groups is least divergent in Bangladesh and most divergent in Nepal. Sri Lanka has witnessed the greatest convergence in upward mobility between historically advantaged and disadvantaged social groups.

The descriptive evidence presented in this paper provide insights to anchor policy efforts addressing persistence of socio-economic deprivation across generations in South Asia. For more information, please see the paper.

We have made all the data from this project public and open source: a harmonized dataset of thirty-nine national representative household surveys with matched parent-child education attainment for India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. To access the open data, click here, or to view the associated metadata, click here.

If you use these data, please cite our paper:

@Unpublished{ abbn2022intergenerational,

author = {Asher, Sam and Bhowmick, Aditi and Bussolo, Maurizio and Novosad, Paul},

note = {Working Paper},

title = {{Intergenerational Mobility in South Asia}},

year = {2022}

}

This project was funded by the World Bank South Asia Chief Economist’s office. Idaliya Grigoryeva, Alison Campion and Nele Warrinier provided research assistance on this project.